Dingus and Dofus, there. Hopefully they'll be more enthuastic about the coloring part the second time around.

-D.d...

Dingus and Dofus, there. Hopefully they'll be more enthuastic about the coloring part the second time around.

-D.d...

A pretty kick-ass installment of Dr. Who, of which I've been watching a lot lately, courtesy my public library. Turns out they have pretty much the entire Tom Baker run (that's been re-released on DVD, and sadly, 'Underworld,' the very first Dr. Who I saw, EVER, is not on that list), as well as a smattering of other Doctors and also the new series. So my viewing needs when the missus is away at work and the brood are asleep are taken care of.

-D.d.

Looking forward to finishing AKIRA, and have been meaning to read more Blaylock.

With other recent purchases these should keep me occupied for a bit.

saute onions, mix into mashed beans and other ingredients. Form into patties and fry til brownish on both sides.

DE: [...] in the early 70s, you joined the Coast Guard. The Coast Guard?-d.d.

JS: I was in the Coast Guard in Portland. I joined it like joining the Foreign Legion because my girlfriend left me for a certain corrupt, sex-addicted guru. I never did quite get over her. I found the Coast Guard to be totally unsuitable for me and me for it, BUT it was a very good, seasoning thing for me [...].

DE: And in Portland you got into punk rock?

JS: I was in the punk band SadoNation in Portland, as lead singer, and then went to New York City and started Obsession. Basically punk saved my ass, it gave me an alternative identity to the tortured and unacceptable one I'd sewn raggedly together; it gave me a forum for reacting to things like the My Lai massacre and the industrialization of America, the "mini-malling" of America, the tract-housing of America.

New York was both glorious and depressing. I'd have done much better there if I hadn't got side tracked into drugs. The needle, later the glass pipe. Drugs leach away the energy of life-direction. But the East village was a place of inspiring ferment. People like Basquiat and the early Beastie Boys and Karen Finlay and Nick Cave were around. [...]

DE: All this time you were writing. Getting published in magazines like Amazing and Fantastic and anthologies edited by people like Terry Carr and Robert Silverberg?

JS: They tried to give me direction, give me outlets. They bought stories, tried to hammer my spiky manner and undisciplined style into something more artful and crafted, God bless them for trying. Ted White and Silverberg and Carr and Jim Frenkel and Ellen Datlow especially helped.

Other writers would throw a really good, cunningly aimed fastball at the editorial catchers; I'd fire a roman candle at the editors and usually they'd duck and swear at me. Roman candles are bombastically pretty and make a great noise, but they fly crookedly, after a moment, and they burn out quickly.

Still, since I was prolific, some of it came out, more or less satisfactorily. [...] But I had no understanding of professionalism. I had no social graces, was a compulsive womanizer -- which didn't help me make friends; but then my wife at the time liked women, too. We were strange people. I was childishly manipulative -- and, worse, clumsy at trying to manipulate people -- people winced at my swaggering; but I wasn't a cowardly, colorless nerd either.

The thing is I really did come from the streets, so where I came from it was right and natural to say anything to try to hustle something up. Truth or lies, it was all the same because you were trying to hustle the squareheads. I had punk damage, too, and thought that doing things professionally was selling out or something.

DE: [...] in the early 80s you met up with these SF writers: William Gibson, who you met at a convention in Vancouver and recommended to Terry Carr and Robert Sheckley; Rudy Rucker, Lew Shiner, Richard Kadrey, Bruce Sterling. Sterling edited a samizdat -- a one page newsletter -- called Cheap Truth, in which you guys (self-named "the Movement") attacked mainstream science fiction and pushed your own version of SF. This "movement" was later dubbed "cyberpunk," of course. What was your role in this?

JS: I only contributed a little to Bruce's brilliant broadsheet, but in public, at conventions, on panels, I was, quite often, the point man; or flailing away at Bruce's side. I'd say ANYFUCKINGTHING. We wanted a science fiction that was open to other cultural influences, like, yes, punk, like modern art, like surrealism, like the more artful noir films and fiction, and people like William Burroughs; and we wanted to dilate the iris of SF so that it took in more sheer FUTURE. I think Bruce felt that most SF was cowardly in its vision of the future. It was coy, winsome, mild mannered, or when it had energy it was oriented toward the kind of guys who took fencing lessons (I love you, Tim Powers, I don't mean you) and dressed up like the characters in the original book Starship Troopers and what have you. Pathetic beer hoisting pot-bellied fannish "macho."

DE: Part of being the "real punk" in cyberpunk was being obnoxious. There are all these stories about you from SF cons: tossing over panel tables, assaulting editors verbally and sometimes physically, Harlan Ellison challenging you to a duel...

JS: Whoa, wait -- he didn't challenge me to that kind of duel. He thought I'd dissed his writing and he challenged me to a writing duel! [...]

DE: But the other hijinx you were up to didn't do a lot to endear you to people who could help your career.

JS: [...] I only wish those stories were exaggerated rather than under-reported. I don't know, I have regrets about some of it, but on the other hand the whole SF and publishing scene was so DEADLY BORING then and mostly still is now. Hey, just trying to be helpful, ease the boredom! But it was not strategically wise, no. I think to this day I don't get certain writing jobs because of fall-out from that sort of horseplay. And sometimes people take shit too seriously.

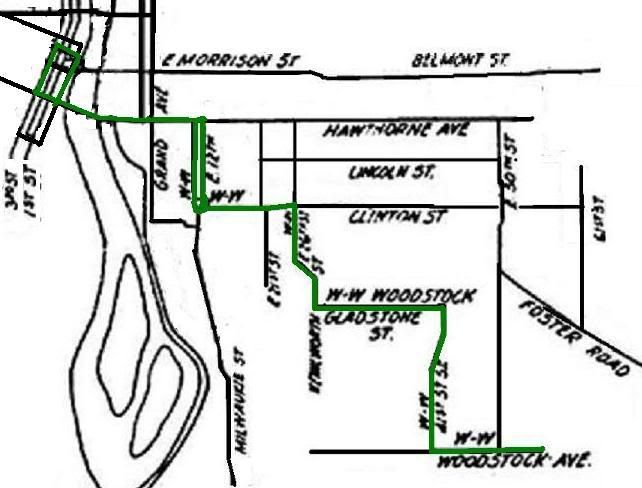

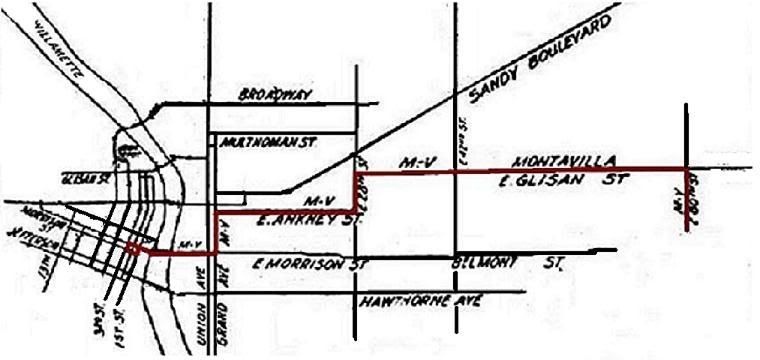

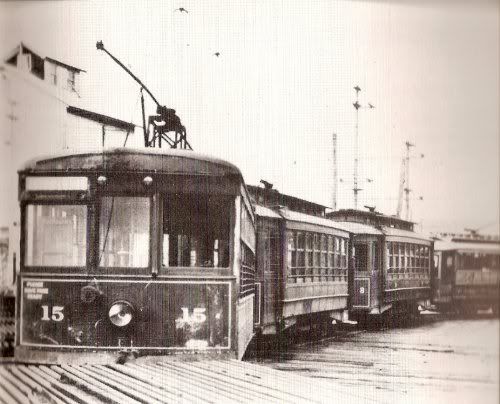

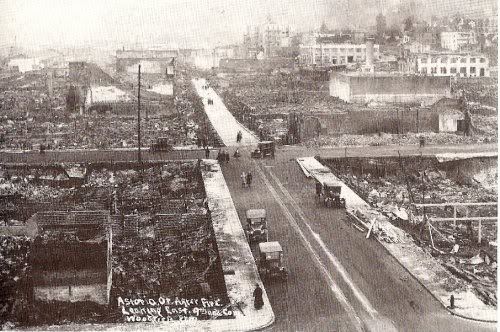

The fourth act in the play of The Astoria Street Railway or, The Connecting Link, a Tale of Scow Bay is now on the stage. The curtain rose on the present comedy last summer when the Astoria Street Railway was organized, and after a brief existence sold the franchise (or rights, whatever they are) to F. P. Hennessy, a pleasant spoken gentleman from across the sea, who with his associates constituted the company that, purely as a matter of benevolence, was going to build a street railway from Uppertown down the roadyway to Squemoqua Street1, and from there the Lord knows where. The evident inability on Mr. Hennessy's part caused the scheme to collapse. All that remains is an uptorn roadway, and unpaid creditors. Among others who took hold in good faith was Pierre Bronsdon, builder of the Portland street railway. He worked one month for free and paid his own board, whereupon he secured the franchise from Hennessy on February 7, 1885.2Astoria's trolleys thus got off to a shaky start.

I will never make fun of the cuisine of the British Isles again.start toasting twothree pieces of breadmelt 1 tablespoon (eighth of a stick) butter in a small saucepan on medium low heat til it starts to froth a bit. Turn the heat down to real low add 1 tablespoon of flour. Mix til the flour and butter have combined in the manner of a sauce. add 1/4th cup of milk, stir til you have a consistent sauce again. Add another 1/4 cup milk and repeat. Add a cup of shredded or finely chopped cheddar cheese. stir til the cheese has melted into the sauce. Add pepper to taste. Add a pinch of cayenne if you want. I put a bunch of Tapatio hot sauce in mine - just make sure its not Tabasco or some shit like that where its just vinegar. take your toast, butter it, put on a big plate. Pour the sauce all over it. I eat mine with a fork (this is what I call a meal) but I guess you could eat it with you hands too Prob a killer post-drinking meal. I haven't tried it yet, but you can substitute beer for the milk also, you can add, like, some beans or chopped tomato to the mix.

Popshifter: Is working on The Venture Bros. something you find difficult?-d.d.

Thirlwell: It exercises different creative muscles, sometimes, those of “problem solving.” It’s made me better in some ways. As I said, I work way in advance so I’m never rushing at the eleventh hour. I don’t consider it a “day job.” It’s a different part of my career and legacy. I established a musical vocabulary and identity for the show.

As for the work process, first I get a copy of the animatic (which is the storyboard edited with camera moves and the dialog embedded in it). I watch it and block out musical ideas, sometimes re-editing cues I’ve already written, and make notes for new compositions. I sync them up then view it with the director Chris McCulloch. We talk about what works and what doesn’t. Since we are watching essentially an animated storyboard, sometimes its not always clear what’s going on in the action to me.

We also discuss the character’s motivation, back-story and exposition, and the subtle subtext of each individual joke. Then I get to work creating the score and afterwards we review it again and I tweak it.

Popshifter: How did you get involved writing for the Arcana book series?

Thirlwell: John Zorn edits and publishes the Arcana books, which consist of musicians writing about music. He invited me to write an essay. The essay I wrote is about tinnitus.7

Popshifter: […] you seem to have an obsession with afflictions or medical contexts. . . are you a total hypochondriac, or […] did you stumble upon a medical textbook you just can’t put down once you start reading it?

Thirlwell: Yes, names of afflictions are a thread in my work. I’m not sure why I’m drawn to them but part of it is the linguistics and the endings. I also like words with “X” in them. I have several threads in my work, including the color palettes that I choose and the monosyllabic four-letter title.

Popshifter: Are the pretty ones really always insane? If that’s the case, then why bother?

Thirlwell: Because they are the ones that hypnotize.